Textus Receptus: A detailed examination of its history, significance, and sources

The Textus Receptus, translated from Latin as “Received Text,” is a foundational collection of the Greek New Testament. This text holds significant historical and theological importance, especially in the context of Western Christianity up to the 19th century.

Content

Origin of the Name

The term “Textus Receptus” was first used in the preface of an edition of the Greek New Testament published in 1633. This edition was published by printers Bonaventura and Abraham Elzevier in Leiden. In the preface, it stated: “Textum ergo habes, nunc ab omnibus receptum, in quo nihil immutatum aut corruptum” – which translates to: “Therefore you have the text now received by all, in which nothing has been changed or corrupted.”

Ursprüngliche Quellen

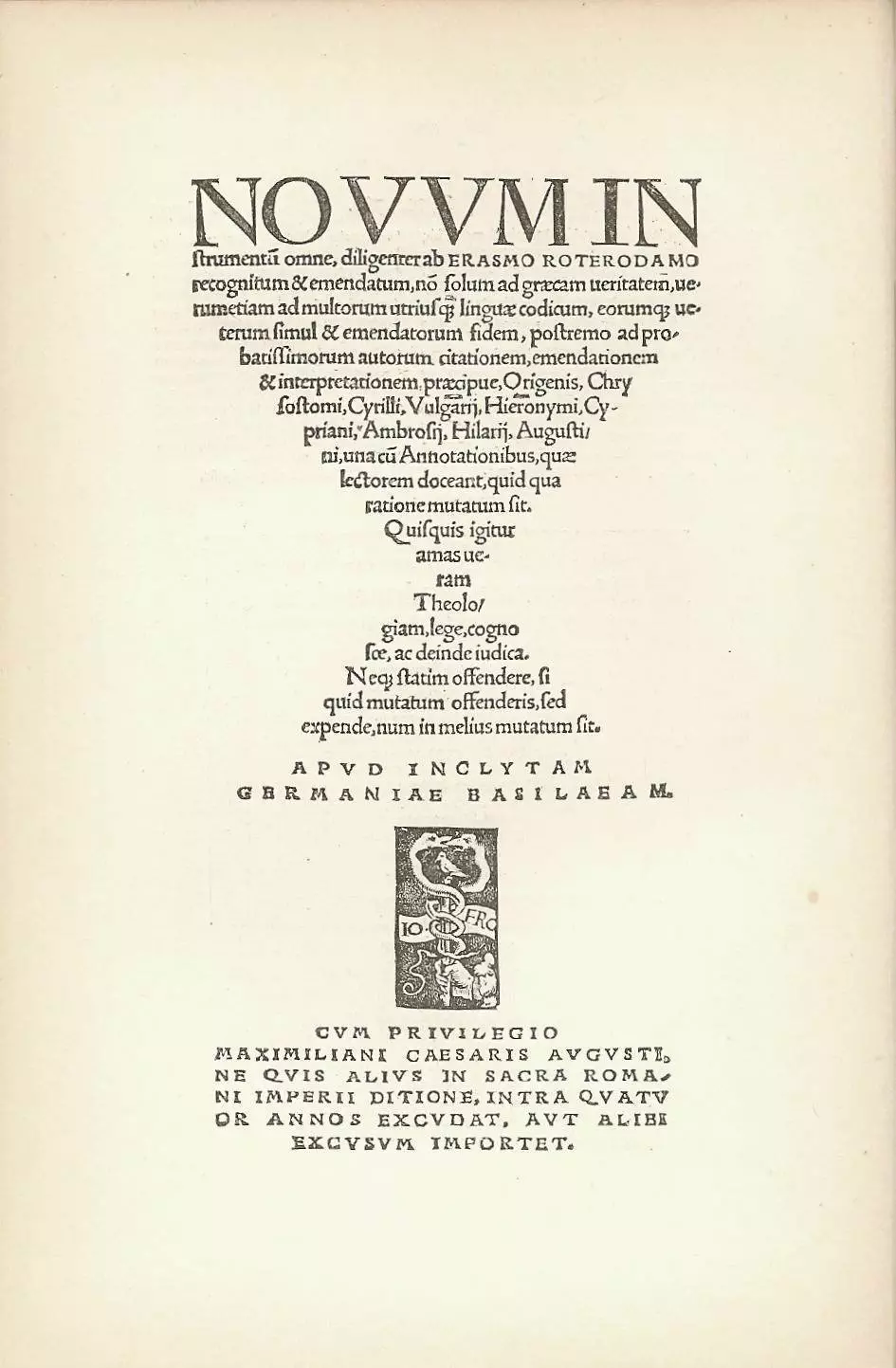

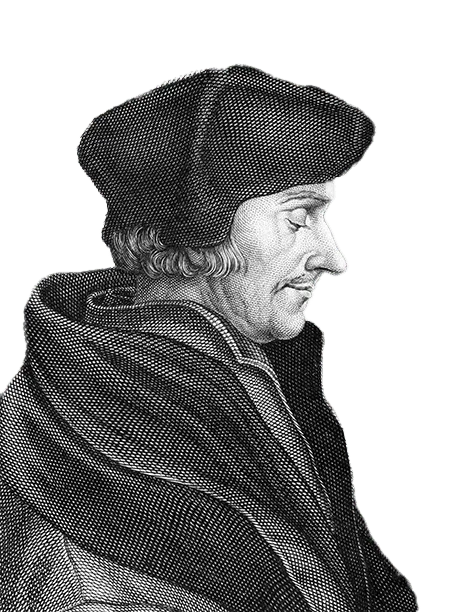

Erasmus of Rotterdam presented the first printed edition of the Greek New Testament in 1516, titled “Novum Instrumentum omne.” For this work, he had access to seven Greek manuscripts of the New Testament, which can be attributed to the Byzantine Majority Text and date from the 11th to the 15th century. Erasmus also used the Latin Vulgate and quotes from the works of the Church Fathers as additional sources.

Stages of Development

Due to the quick production time of only five months, Erasmus’ first edition contained many errors. A revised version was published in 1519 and served as the basis for Martin Luther’s German translation of the New Testament. Further editions with text corrections were published in the years 1522, 1527, and 1535.

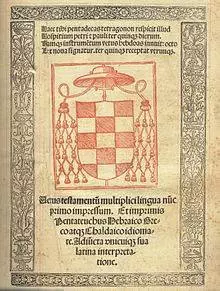

Before Erasmus published his edition, Cardinal Jiménez in Spain had already prepared the multilingual Complutensian Polyglot. However, it was not published until 1520.

Robert Estienne, auch bekannt als Stephanus, publizierte 1546 eine textkritische Ausgabe, die auf den Werken von Erasmus und der Complutensischen Polyglotte basierte. His third edition of 1550 became known as the “Editio Regia.” With the fourth edition, Estienne also introduced the verse numbering system still used in the New Testament today.

Textual Critical Classification

Textual criticism research identifies different text families of the New Testament. The Textus Receptus shows many similarities with the Byzantine text but is not considered the best representation of this text family due to the limited number of manuscripts used. In the 19th century, additional manuscripts were discovered that questioned the Textus Receptus.

Current Use and Influence

While modern Bible translations mostly rely on newer text-critical editions like the “Novum Testamentum Graece” or the “Greek New Testament,” the Textus Receptus continues to be used in certain Christian communities, especially in non-denominational and evangelical circles. The Greek Orthodox Church also uses a text that is very similar to the Textus Receptus.

Overall, the Textus Receptus has had a significant impact on the Christian world and continues to influence some Bible translations and interpretations of the New Testament to this day.

Overall, the Textus Receptus has had a significant impact on the Christian world and continues to influence some Bible translations and interpretations of the New Testament to this day.

The Chronology of the Textus Receptus: From Erasmus to Modern Textual Criticism

First edition by Erasmus

Erasmus of Rotterdam publishes the first edition of the Greek New Testament under the title “Novum Instrumentum omne.” Seven Byzantine manuscripts from the 11th to the 15th centuries form the basis.

Second edition by Erasmus

A revised version is published, which later serves as the basis for Martin Luther’s German translation of the New Testament.

Complutensian Polyglot

The Complutensian Polyglot, a multilingual Bible project under the direction of Cardinal Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros, begins its work in Alcalá, Spain, in 1502. The goal is to compile a meticulous edition of the biblical texts in their original languages – Hebrew, Greek, Latin, and Aramaic. Although the editorial work is completed in 1517, it takes until 1522 to receive approval from the Catholic Church for publication. In the meantime, Erasmus of Rotterdam publishes his “Novum Testamentum” in 1516, which quickly gains influence. The Complutensian Polyglot is eventually published, but with less influence than Erasmus’ work, as it is released later despite being created earlier. However, it remains a significant work for textual criticism and biblical studies.

Erasmus' third edition corrects critical errors.

The third edition of Erasmus’ Greek New Testament is published. In this edition, Erasmus makes numerous corrections to address the errors found in the first two editions. The changes mainly reflect the feedback from scholars and theologians who had critically reviewed the first editions.

Erasmus and the controversial inclusion of the Comma Johanneum in the Textus Receptus

Erasmus' fourth edition adds more textual variants.

In the fourth edition of Erasmus’ Greek New Testament, additional textual variants and comments are introduced. Erasmus refers to additional manuscripts and scholarly opinions to improve and expand his text.

The final refinement of the text by Erasmus

The fifth and final edition of Erasmus’ Greek New Testament is published. This edition is considered the most mature and later becomes one of the main sources for the Textus Receptus. Erasmus makes final corrections and adjustments that will shape his text for future generations.

First edition Novum Testamentum Graece - Robert Estienne (Stephanus)

The first text-critical edition by Robert Estienne is published, based on Erasmus’ text and the Complutensian Polyglot.

In his first edition of the Greek New Testament, Estienne combined various Greek manuscripts without directly citing Erasmus. This edition was one of the earliest text-critical efforts and represented a significant improvement over earlier versions.

Second edition Novum Testamentum Graece - Robert Estienne (Stephanus)

The second edition, also in Greek, built upon the work of the first edition and further improved it. Unfortunately, specific details about the changes in this edition compared to the first one are not precisely documented.

Editio Regia

The third edition, known as the “Editio Regia” or “Royal Edition,” was a masterpiece of typographical skill and included a critical apparatus where manuscripts referring to the text were marked by symbols (from α to ις). Estienne used the Complutensian Polyglot and 15 Greek manuscripts, including the Codex Bezae and the Codex Regius. This edition became known as the “Textus Receptus,” which served as the standard text for many generations.

4th edition - Robert Estienne (Stephanus)

In the fourth edition, published in Geneva, Estienne introduced the division of the New Testament into chapters and verses for the first time. This edition also included the Latin translation by Erasmus and the Vulgate. It is particularly rare and marked a significant step in the history of Bible printing.

King James Version (KJV)

The English KJV Bible is published, based on the Textus Receptus, and becomes one of the most influential Bible translations.

Term "Textus Receptus" coined

The term “Textus Receptus” is first used in the edition of the Greek New Testament by Bonaventura and Abraham Elzevier.

Emerging criticism

Textual critics begin to question the accuracy of the Textus Receptus, especially in light of new manuscript discoveries.

Westcott and Hort

Brooke Foss Westcott and Fenton John Anthony Hort publish a new edition of the Greek New Testament, questioning the Textus Receptus and initiating a departure from it.

Modern textual-critical editions

With the publication of the Nestle-Aland and the United Bible Societies (UBS) Greek New Testament, the Textus Receptus is largely displaced in the scholarly community but continues to be used in certain churches and communities.

Novum Testamentum Omne

Erasmus’ Novum Instrumentum Omne, later known as Novum Testamentum Omne, was a bilingual Latin-Greek edition of the New Testament with scholarly annotations and the first printed edition of the Greek New Testament. It was prepared by Desiderius Erasmus (1466–1536) and printed by Johann Froben (1460–1527) from Basel. Five editions were published: 1516, 1519, 1522, 1527, and 1536. It is estimated that up to 300,000 copies of Erasmus’ New Testament were printed during his lifetime.

The first edition of 1516, titled Novum Instrumentum Omne, included Erasmus’ revision of the Latin Vulgate as more classical Latin; in subsequent editions, it evolved into an independent Latin version influenced by the Greek. The Greek text is a Byzantine text type. The work was reissued in a second edition (1519) under the new title Novum Testamentum Omne, which was used by Martin Luther for his translation of the New Testament into German (the so-called “September Testament”). The third edition (1522) was used by William Tyndale for the first English New Testament (1526). The Erasmian editions and subsequent revisions in the 16th century influenced the Geneva Bible (1560), the King James Version (1611), and the Textus Receptus, which formed the basis for most modern translations of the New Testament in the 16th to 19th centuries.

Among the contemporary efforts was the translation of the New Testament from Greek and the Psalms from Hebrew by Giannozzo Manetti at the court of Pope Nicholas V, around 1455. The manuscripts still exist, but Manetti’s version was only printed in 2014. Greek fragments began to be printed when Greek fonts were cut: The Aldine Press published the first six chapters of the Gospel of John in 1505. In the early 1500s, there were several authorized efforts to create and publish scholarly polyglot and Greek editions of the biblical texts. In 1512, the French priest Jacques Lefèvre d’Étaples published his revised version of the Pauline Epistles of the Vulgate, corrected against Greek texts, as well as a fourfold translation of the Psalms supported by Cardinal Briçonnet. In Spain, Cardinal Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros assembled a team of Spanish translators in 1502 to create a compilation of the Bible in four languages: Greek, Hebrew, Aramaic, and Latin. Translators from Greek were commissioned from Greece and worked closely with Latinists. In addition to compiling the Bible, there was a new Latin text created for the Vulgate. This text, much of which had already been translated from Greek by the Church Father Jerome in the 4th century, was considered the only authoritative translation in the Catholic Church and was used instead of a new translation. Cisneros’ team completed and printed the entire New Testament, including the Greek version, in 1514. They also developed special fonts for printing Greek. Cisneros informed Erasmus about the work in Spain and possibly sent him a printed version of the New Testament. However, the Spanish team intended to publish the entire Bible as a single work and withdrew from the publication. Even though the first printed Greek New Testament was the Complutensian Polyglot (1514), Erasmus’ work was published first (1516). Erasmus was invited by Cisneros in 1517 to collaborate on the Complutensian Polyglot edition and to offer him a bishopric. But the Dutchman stayed and never traveled to Spain. The Complutensian Polyglot edition was approved for publication by the Pope in 1520; however, it was not published until 1522 due to the team’s persistent desire for review and editing.

In his dedication to Pope Leo X, Erasmus described his editorial approach with the (Latin) New Testament as philological rather than theological: “to fill the gaps, to soften the abrupt, to digest the obscure, to develop the developed, to explain the intricate, to shed light on the dark, to give a Roman polish to the Hebrew expressions… and thus moderate παραφρασιννε παραφρόνησις: that is, ‘to say differently in order not to say differently.'” He polished the Latin and explained: “It is only fair that Paul should address the Romans in somewhat better Latin.” Erasmus’ Latin contained some controversial translations – unlike the Vulgate – with philological or historical justifications in the notes on words that played a significant role in the Reformation.

According to scholars like Henk Jan de Jong, Erasmus’ Greek text in his editions of the New Testament was not intended as a standalone critical text but rather to provide the reader of the Latin version with the opportunity to determine if the translation was supported by the Greek text. To some extent, Erasmus “synchronized” or “harmonized” the Greek (Byzantine) and Latin textual traditions of the New Testament by simultaneously creating an updated translation of both. Since both were part of the canonical tradition, he obviously considered it necessary to ensure that both actually contained the same content. In modern terminology, he made the two traditions “compatible.” This is clearly evident in the way his Greek text informs his Latin translation, but also vice versa: there are numerous instances where he edits the Greek text to reflect his Latin version (and possibly some lost Greek or patristic sources from his earlier research), or where he simply preferred the reading of the Vulgate to that of the Greek text (e.g. at). Acts 9:6).

bibletranslations

Luther Bible (1522, New Testament)

Martin Luther used the second edition of Erasmus’s Textus Receptus for his translation of the New Testament.

Tyndale Bible (1526, New Testament)

William Tyndale’s translation of the New Testament into English was also based on the Textus Receptus.

Geneva Bible (1560)

An English translation created by the Reformers in Geneva.

Bishops’ Bible (1568)

This English Bible was an attempt to replace the Tyndale and Geneva Bibles and served as the basis for the King James Bible.

King James Version (KJV) (1611)

One of the most well-known English-language Bibles based on the Textus Receptus.

Textus Receptus-based translations into other languages

This includes the Spanish Reina-Valera (1602), the French Louis Segond (1910), and the Portuguese Almeida (1681).

Young’s Literal Translation (YLT)

A literal English translation of the Bible text that also utilizes the Textus Receptus.

New King James Version (NKJV)

Although more modern, this translation seeks to remain faithful to the original text of the KJV and considers the Textus Receptus.

21st Century King James Version (KJ21)

An update of the KJV that retains the Textus Receptus as its foundation.

Byzantine text form

Some newer translations, especially in non-denominational and evangelical circles, utilize a form of the Byzantine text that is very similar to the Textus Receptus.

The Greek Orthodox Church

The liturgical use of the Greek New Testament in the Greek Orthodox Church is based on a text that is similar to the Textus Receptus.

Byzantine Manuscripts: Erasmus had access to seven manuscripts of the Greek New Testament. These manuscripts date from the 11th to the 15th century and belong to the tradition of the Byzantine Majority Text.

Famous Manuscripts

Minuscule 1: A manuscript from the 12th century that is currently housed in the University Library of Basel. It contains the entire New Testament and was one of the main sources for Erasmus.

Minuscule 2: Another manuscript from the 12th century that Erasmus used. It is also preserved in the University Library of Basel.

Minuscule 3: A manuscript from the 12th century that contains only parts of the New Testament. It is also preserved in Basel.

Minuscule 4 and 5: Two other manuscripts available to Erasmus, but their specific details are less well-documented.

The Vulgate: In addition to the Greek manuscripts, Erasmus also consulted the Latin Vulgate as a reference, especially for the parts of the New Testament for which he did not have Greek manuscripts.

Biblical Quotations in the Church Fathers: Erasmus also used quotes from the New Testament that he found in the works of the Church Fathers as an additional source of information.

Origin of the Sources:

The seven Byzantine manuscripts that Erasmus used were available in various European libraries and monasteries. Since printing was still in its infancy at that time, manuscripts were a precious resource that were mostly kept in such institutions.