Codex Leningradensis B19A: The oldest preserved manuscript of the Old Testament

The Codex Leningradensis B19A is one of the oldest fully preserved manuscripts of the Tanakh, the Hebrew Bible. It dates back to the year 1008 AD and is kept in the Russian National Library in St. Petersburg, formerly known as Leningrad until 1991, from which the name of the Codex is derived. The Codex follows the Masoretic tradition, distinguished by a special system of vocalizations and accents to ensure the correct reading of the Hebrew text. It serves as the basis for many modern editions of the Old Testament and is an important tool for textual critics and biblical scholars due to its age and completeness.

The Leningrad Codex: The Oldest Complete Manuscript of the Hebrew Bible and Its Significance for Textual Criticism

The hypothesis that the Leningrad Codex originated from corrections made to the Aleppo Codex, a slightly earlier manuscript, is questioned by Paul E. Kahle. He argues that the manuscript likely is based on other manuscripts from the ben Asher family, which are now lost. Due to losses suffered by the Aleppo Codex during anti-Jewish riots in 1947, the Leningrad Codex represents the oldest fully preserved work of the Tiberian Masorah.

The Leningrad Codex finds its home in the National Library of Russia in St. Petersburg. The library, an important hub for scholarly research and culture, has been safeguarding the Codex since the late 19th century as part of an extensive collection of Hebrew manuscripts that are of immense importance for Hebraic and Judaic studies.

The Leningrad Codex served as the textual basis for various editions of the Hebrew Bible, including the Biblia Hebraica (1937), the Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia (1977), and the ongoing series of the Biblia Hebraica Quinta (from 2004). It also plays a key role in reconstructing the missing parts of the Aleppo Codex.

The manuscript includes the Hebrew base text, supplemented with Tiberian vocalization and cantillation marks. Furthermore, Masoretic notes can be found in the margins. Written on parchment and bound in leather, the Codex includes the following sequence of biblical books:

The Torah:

1. Mose (Genesis) / Genesis [בראשית / Bereishit]

2. Mose (Exodus) / Exodus [שמות / Shemot]

3. Mose (Leviticus) / Leviticus [ויקרא / Vayikra]

4. Mose (Numeri) / Numbers [במדבר / Bamidbar]

5. Mose (Deuteronomium) / Deuteronomy [דברים / Devarim]

The Nevi’im:

- Josua / Joshua [יהושע / Yehoshua]

- Judges / Judges [שופטים / Shofetim]

- Samuel (I & II) / Samuel (I & II) [שמואל / Shemuel]

- Kings (I & II) / Kings (I & II) [מלכים / Melakhim]

- Isaiah / Isaiah [ישעיהו / Yeshayahu]

- Jeremiah / Jeremiah [ירמיהו / Yirmiyahu]

- Ezekiel / Ezekiel [יחזקאל / Yehezqel]

- The Twelve Prophets / The Twelve Prophets [תרי עשר]

- Hosea / Hosea [הושע / Hoshea]

- Joel / Joel [יואל / Yo’el]

- Amos / Amos [עמוס / Amos]

- Obadiah / Obadiah [עובדיה / Ovadyah]

- Jonah / Jonah [יונה / Yonah]

- Micah / Micah [מיכה / Mikhah]

- Nahum / Nahum [נחום / Nahum]

- Habakkuk / Habakkuk [חבקוק / Habakuk]

- Zephaniah / Zephaniah [צפניה / Tsefanyah]

- Haggai / Haggai [חגי / Hagai]

- Zechariah / Zechariah [זכריה / Zekharyah]

- Malachi / Malachi [מלאכי / Mal’akhi]

The Writings:

- Chronicles (I & II) / Chronicles (I & II) [דברי הימים / Divrei Hayamim]

- Psalms / Psalms [תהלים / Tehilim]

- Job / Job [איוב / Iyov]

- Proverbs / Proverbs [משלי / Mishlei]

- Ruth / Ruth [רות / Rut]

- Song of Songs / Song of Songs [שיר השירים / Shir Hashirim]

- Ecclesiastes / Ecclesiastes [קהלת / Kohelet]

- Lamentations / Lamentations [איכה / Eikhah]

- Esther / Esther [אסתר / Esther]

- Daniel / Daniel [דניאל / Dani’el]

- Ezra-Nehemiah / Ezra-Nehemiah [עזרא ונחמיה / Ezra ve-Nehemiah]

Therefore, the Leningrad Codex becomes an indispensable historical and textual-critical tool for the study of the Old Testament and serves as the basis for modern translations and editions.

Development and Significance of the Leningrad Codex: A Journey Through Time

Transition to codices

Christian scholars begin to transcribe their sacred works into codices instead of scrolls. Jews follow this trend only in the 7th century.

Introduction of the codex in Judaism

In Judaism, codices are introduced for sacred texts instead of scrolls.

Leningrad Codex is created

The Leningrad Codex, often simply abbreviated as “L,” was penned by the scribe Samuel ben Jacob (Shemu’el ben Ya’akov) in Cairo. It represents the oldest extant complete manuscript of the Hebrew Bible.

According to the colophon of the manuscript, it was completed in the year 1008 AD. This makes it one of the most important sources for the Masoretic Text of the Old Testament.

Despite the colophon’s statement, there are scholarly voices that mention the year 1010, based on different interpretations of the Masoretic notes and other secondary sources.

However, the majority of scholarly literature tends to accept the year 1008 mentioned in the colophon as the year of the Codex’s creation.

Acquisition and Donation

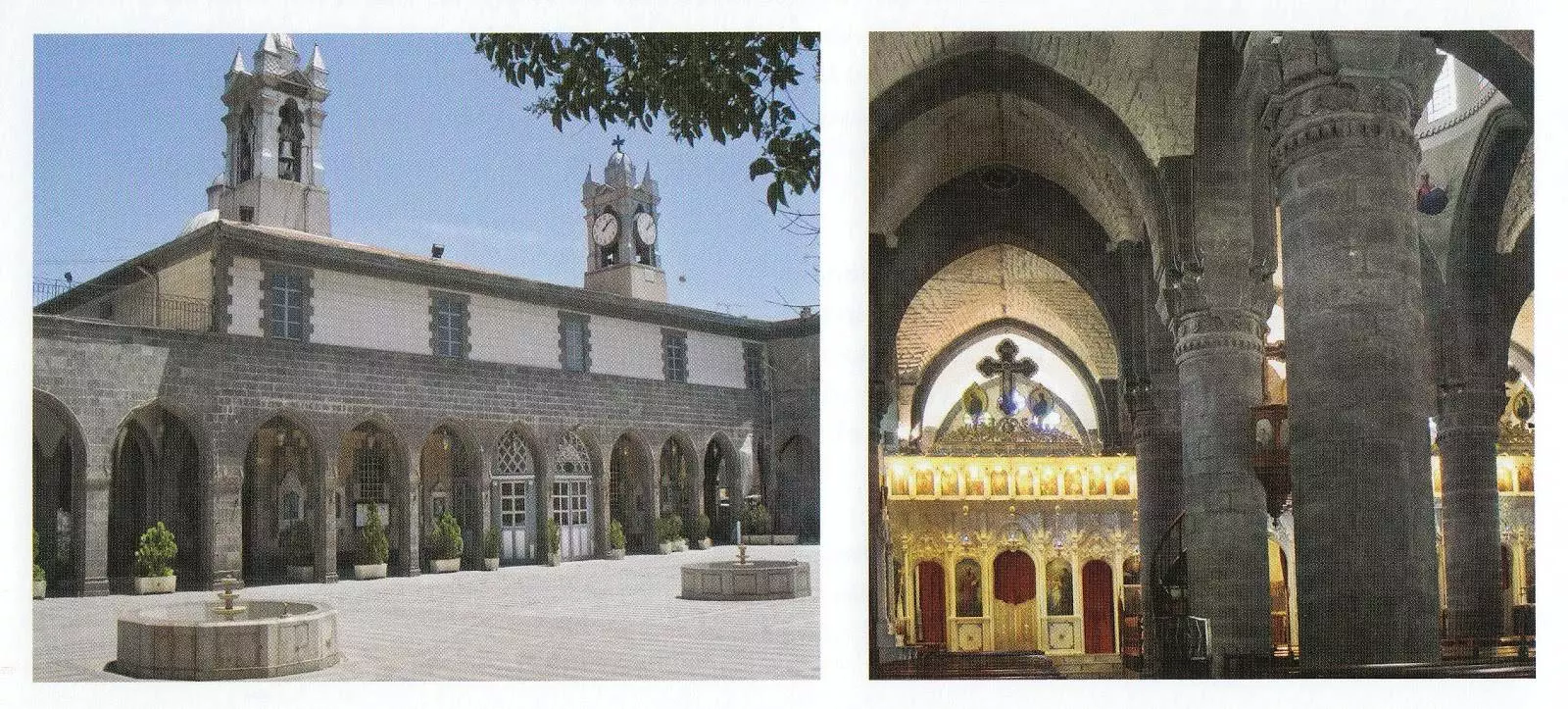

The codex is acquired by a yeshiva leader and donated to the Karaite synagogue in Damascus three months later.

This synagogue was located in the Old City, south of the Straight Street and near the Eastern Gate (Bab Sharqi). In 1832, it was sold and converted into the al-Zeitoun Church. The building was destroyed in 1860 but rebuilt in 1863 and now serves as the Melkite Cathedral.

The Karaites are a Jewish religious community that heavily relies on the Hebrew Bible as the sole source of divine revelation. Contrary to Rabbinic Jews, they reject the oral tradition and the Talmud. This distinction makes them a unique sect within Judaism.

Abraham Firkovich

Firkovich, a Karaite, acquires the Leningrad Codex. The exact circumstances are unknown.

Abraham Firkovich was born on September 27, 1786, in Lutsk, Volhynia, and was a renowned Karaite writer, archaeologist, and collector of ancient manuscripts. He collected a variety of Hebrew, Arabic, and Samaritan manuscripts during his numerous travels. His collections encompass thousands of Jewish documents from across the Russian Empire.

Abraham Firkovich’s collections, including the First Firkovich Collection and the Second Firkovich Collection, are now housed in the Russian National Library in St. Petersburg. They constitute an invaluable source for biblical scholars and historians, especially those studying the Karaite and Samaritan communities.

Abraham Firkovich’s life and works are of great significance to the history and literature of the Karaites. His collections provide valuable insights into the traditions and history of his people. While controversies persist and some of his discoveries are questioned, his contributions to Jewish studies remain significant.

Renaming of the city and the library

After the Russian Revolution, Petrograd (formerly Saint Petersburg) is renamed Leningrad, and the former Imperial Public Library becomes the National Library of Russia.

Study in Leipzig

Paul Kahle and his student Gottfried Quell study the Leningrad Codex in Leipzig.

Loan to Leipzig University

The Leningrad Codex is loaned to the Old Testament Seminar of Leipzig University for two years.

Biblia Hebraica (3rd edition)

The Leningrad Codex serves as the base text for the third edition of the Biblia Hebraica (BHK).

The first two editions of the Biblia Hebraica (1906, 1912), edited by Rudolf Kittel, were rather loosely based on the Codex from Petrograd, also known as Codex Leningradensis. In the third edition and the subsequent Biblia Hebraica Stuttgartensia, this codex was more precisely used as the base text. The more detailed focus on the Leningrad Codex in the later editions is based on its role as the oldest complete manuscript of the Masoretic Text of the Old Testament.

Biblia Hebraica (4th edition)

The Leningrad Codex remains the base text for the fourth edition of the Biblia Hebraica (BHS).

Glasnost and access

Thanks to Glasnost, Western scholars gain access to the Leningrad Codex. Photographs are taken.

New photographs

A team from California re-photographs all 982 pages of the Leningrad Codex.

Facsimile edition

A facsimile edition of the Leningrad Codex is published by Eerdmans.

JPS Hebrew-English Tanakh

The JPS Hebrew-English Tanakh and the various volumes of the JPS Torah Commentary and JPS Bible Commentary use the Westminster text based on the Leningrad Codex.

Biblia Hebraica (5th edition)

The fifth edition (BHQ) is based on the Leningrad Codex.

Russian National Library

The Leningrad Codex (Codex Leningradensis B19A) is housed in the Russian National Library in St. Petersburg. The library has had the Codex in its collection since the late 19th century.

It has been kept there as part of a larger collection of Hebrew manuscripts that are invaluable for the study of the Hebrew language and Judaism. The library itself is an important hub for scholarly research and culture, providing access to a variety of resources that are of interest to students, researchers, and academics.

Interactive viewing of the Leningrad Codex

The digitization of the Leningrad Codex was first done in 2011 and is licensed under the Public Domain Mark 1.0, making it freely accessible. It is part of an extensive collection of books in the Hebrew language, allowing interested individuals to study this important work online.

For direct access to the digitized version of the Leningrad Codex, you can visit the official page on Archive.org or alternatively use the embedded version directly here.