Other Masoretic texts, such as Codex Cairensis and Codex Orientalis

This page provides an overview of various Masoretic texts, including lesser-known manuscripts like the Cairo Codex and the Erfurt Codices. In addition to these, other relevant texts in the Masoretic tradition are also presented. The focus is on the textual critical significance of these manuscripts for the Old Testament. Information about the history of these texts and their current locations is also provided. The guide aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the Masoretic textual landscape.

Content

The Cairo Codex: A Detailed Look

The Cairo Codex, also known as the Codex Prophetarum Cairensis or Cairo Codex of the Prophets, is a significant cultural and historical artifact of invaluable worth. This Hebrew codex contains the complete text of the Nevi’im (Prophets) from the Hebrew Bible and has a rich history as well as significant scholarly importance.

Historical Context

The Cairo Codex has traditionally been referred to as “the oldest dated Hebrew codex of the Bible that has come down to us.” Its colophon indicates the year 895 CE, although modern research suggests a date closer to the 11th century. The colophon states that the codex was written with punctuation by Moses ben Asher in Tiberias “at the end of the year 827 after the destruction of the second Temple.”

Interestingly, the codex contains the books of the Former Prophets (Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings) and the Latter Prophets (Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and the Book of the Twelve Minor Prophets). With a total of 575 pages, including 13 carpet pages, the extent of the codex is impressive.

Journey of the Cairo Codex

The journey of this historical document through the centuries is as fascinating as its content. Originally, it was given to the Karaite community in Jerusalem. However, during the Crusades in 1099, it was taken as loot. Later, it was redeemed and came into the possession of the Karaite community in Cairo. In 1983, the codex was deposited at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, where it is currently preserved.

Scholarly Evaluation

Despite its historical significance and age, the Cairo Codex has also sparked some controversies. Some scholars have noted that the codex in the Masoretic tradition is closer to Ben Naphtali than to Aaron ben Moses ben Asher. This observation has led some to assume that Ben Naphtali remained more faithful to the system of Moses ben Asher than Aaron ben Moses ben Asher, who corrected the Aleppo Codex and added his punctuation.

Further investigations using modern scientific methods such as radiocarbon dating, however, have raised additional doubts about its authenticity. Scientific investigations seem to indicate that the scribe must have been a different person than the singer and that the manuscript must be dated to the 11th century, not the 9th century.

Meaning and influence

Despite these controversies, the Codex Cairensis remains a valuable artifact and an important source for historians and scholars. For example, Umberto Cassuto heavily relied on this codex when creating his edition of the Masoretic text. Between 1979 and 1992, a team of Spanish scholars published an editio princeps of the codex (text and Masorahs).

The Codex Cairensis is a significant testimony to the history and culture of Judaism as well as to the development of the Hebrew language and script. Its journey through the centuries has bestowed upon it an unparalleled value that is recognized to this day.

Chronology of Events

The creation of the Codex

Moses ben Asher, a renowned scribe and member of a famous family of Masoretes, is mentioned in the colophon as the author of the Codex Cairensis. The creation of the codex was a meticulous task that required not only deep religious and linguistic knowledge but also craftsmanship.

The codex in the First Crusade

During the First Crusade, the codex was taken as loot and thus made its way to Europe. The exact journey of the codex is not documented, but its existence in Europe at that time is undisputed.

The return to Judaism

At an unknown point in time, the codex came into the possession of the Karaite community in Cairo. The Karaites are a Jewish sect known for their strict interpretation of the Hebrew Scriptures.

The arrival in Jerusalem

The Karaite Jews brought the codex with them when they emigrated from Egypt to Jerusalem and deposited it at the Hebrew University, a renowned center for Jewish studies.

Verification of the date

Modern scientific methods like radiocarbon dating and palaeographic examinations suggest that the codex may possibly date back to the 11th century and not to the year 895 as stated in the colophon.

Scientific evaluation

Scholars like Lazar Lipschütz and Moshe Goshen-Gottstein have extensively studied the codex and determined that it aligns more closely with the Masoretic tradition of Ben Naphtali than with Aaron ben Moses ben Asher.

Editio princeps of the codex

An editio princeps of the codex was published. This project was carried out by a team of Spanish scientists, including F. Pérez Castro and his colleagues. They published their work in eight volumes under the title “El Códice de Profetas de El Cairo”.

Current Research

The Codex Cairensis continues to be studied by numerous scholars. Among the notable researchers are the team from the Hebrew University Bible Project, which has analyzed the codex as part of its comprehensive study of the Masoretic text.

Online access

You can view the Codex Cairensis online on the Archive.org platform. This digital library allows you to flip through the individual pages of the manuscript and view its content in high resolution. Furthermore, you can download the entire codex or select pages for your research purposes. Various download options, including PDF and other formats, are available. This is an excellent resource for anyone looking to delve deep into the Codex Cairensis and its significance in the Masoretic text tradition.

Current location

The London Codex or Codex Orientales 4445 (CO)

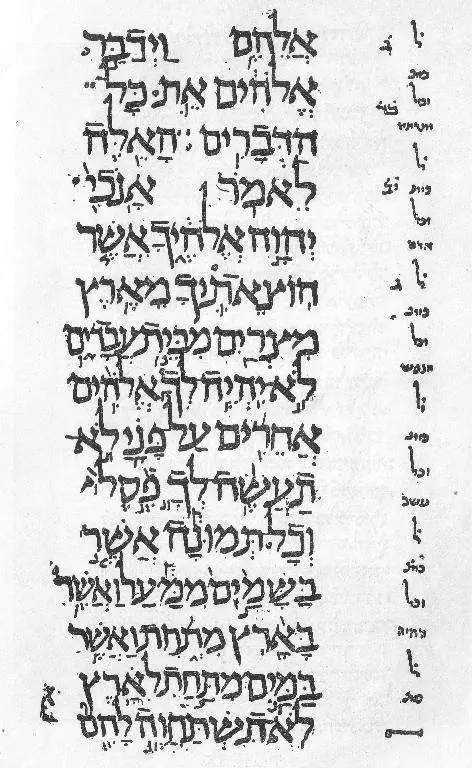

The London Codex, also known as Codex Orientales 4445, represents a significant milestone in the textual history of the Old Testament. Composed in the 10th century, this manuscript contains the Pentateuch, the first five books of the Hebrew Bible. It is equipped with vowel points and accents that clarify the tone and emphasis of the words. In addition, the manuscript contains the Masora Magna and Parva, annotations and comments by Jewish scholars on the Hebrew Bible.

In the year 1539/1540, additional parts were added to the manuscript. These additions are written in a Yemenite square script from the 16th century. Interestingly, the text of this manuscript aligns with the Palestinian or Western recension, which serves as the basis for the Textus Receptus. This distinguishes the London Codex from the Codex Babylonicus Petropolitanus, which is associated with the Babylonian or Eastern recension.

Physically, the London Codex is composed of parchment and paper. The manuscript consists of 186 folios, with leaf dimensions of 418 x 334 mm and a writing area of 284 x 248 mm. The main text is written in a square script from the 10th century.

The provenance of the manuscript is not fully clarified, but it is assumed to originally come from Egypt or Palestine. On May 9, 1891, it found its way into the collection of the British Museum after being sold by Mrs C. D. Sassoon & Co.

The London Codex has received broad academic attention over the years. Scholars like George Margoliouth, Aron Dotan, Maria-Teresa Ortega-Monasterio, Élodie Attia, and Christian D. Ginsburg have made significant research contributions to this manuscript. It stands as a timeless artifact that illustrates the depth of our cultural and religious roots.

Chronology of Events

The creation of the Codex

The London Codex, also known as Codex Orientales 4445, was written in the 10th century. It is a manuscript that contains the Masoretic text of the Pentateuch. Time period of origin: Egypt or Palestine

Addition of parts

In the year 1539/1540, some parts are added to the London Codex. These additions date back to the 16th century.

Sale to the British Museum

On May 9, 1891, the London Codex was sold to the British Museum by Mrs C. D. Sassoon & Co, where it is preserved to this day.

Current storage location: British Museum - London

The British Museum is located in the heart of London, the capital of the United Kingdom. More precisely, it is situated on Great Russell Street in the Bloomsbury district of London. The museum is one of the oldest and most prestigious museums in the world, founded in 1753. It opened its doors to the public in 1759 and has since attracted millions of visitors from around the world.

The British Museum houses one of the most extensive collections of artworks and artifacts, covering a wide range of subjects from antiquity to modern times. It is known for its impressive architecture, including the famous glass dome of the Great Court.

The public transportation connections to the museum are excellent. It is easily accessible by the London Underground, with the nearest stations being Tottenham Court Road and Holborn. Furthermore, there are numerous bus routes that stop nearby.

The Codex Petropolitanus (Codex Babylonicus Petropolitanus)

The Codex Petropolitanus is one of the earliest known Bible manuscripts, dated to the year 916 AD. It contains the Latter Prophets of the Old Testament, namely the books of Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and the Minor Prophets, making it an important testimony to the transmission of these biblical texts.

Originally, the Codex was published by Hermann L. Strack in a facsimile edition and titled “Prophetarum posteriorum Codex Babylonicus Petropolitanus”. Strack chose this title to highlight the use of older Babylonian signs in the Codex, even though the text itself and the Masorah follow the Western (Tiberian) tradition.

The Codex Petropolitanus is part of the Firkovitch Collection, an extensive collection of Jewish manuscripts compiled in the 19th century by the Jewish merchant Abraham Firkovitch. After Firkovitch’s death in 1874, the collection was transferred to the Russian Imperial Public Museum in St. Petersburg, where it is preserved to this day.

A notable feature of the Codex Petropolitanus is its use of the Babylonian vocalization system, which had been lost for a long time prior. These points serve to vocalize the Hebrew text and indicate emphasis and sentence melody. The Babylonian vocalization differs from the Tiberian vocalization used in other significant Bible manuscripts such as the Codex Leningradensis.

Abraham Firkowitsch reportedly discovered the Codex Petropolitanus in 1839, allegedly in the synagogue of Chufut-Kale in Crimea. Its significance lies not only in its age but also in being a valuable testimony to the Babylonian vocalization and providing insight into the textual transmission of the Old Testament.

Today, the Codex Petropolitanus is preserved in the Russian National Library in St. Petersburg and continues to be the subject of intensive scholarly research and textual criticism. Due to its unique textual tradition and historical value, the Codex Petropolitanus contributes to the study of the Old Testament, allowing researchers to better understand the development of the Hebrew Bible text.

Chronology of Events

The creation of the Codex

The Codex Babylonicus Petropolitanus was written in the year 916 AD. This manuscript contains the Latter Prophets of the Old Testament, including the books of Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and the Minor Prophets.

Discovery of the manuscript

In 1839, the Codex Babylonicus Petropolitanus was discovered by Abraham Firkowitsch, allegedly in the synagogue of Chufut-Kale in Crimea.

Publication facsimile edition

In 1866, Hermann L. Strack published the Codex Babylonicus Petropolitanus in a facsimile edition. This important publication was titled “Prophetarum posteriorum Codex Babylonicus Petropolitanus”. The title “Prophetarum posteriorum” refers to the “Latter Prophets” of the Old Testament that are contained in this manuscript. This publication was of great significance for the scholarly research of the manuscript and contributed to the recognition of the Codex.

Transfer to the Russian Imperial Museum

After the death of Abraham Firkowitsch in 1874, the Firkovitch Collection was transferred to the Russian Imperial Public Museum in St. Petersburg, where the Codex Babylonicus Petropolitanus is preserved to this day.

Current storage location: National Library St. Petersburg

The Russian National Library in St. Petersburg is an impressive institution with a fascinating history and a rich collection of Hebrew writings. Founded in 1795, it is one of the oldest and most prestigious libraries in Russia. The majestic neoclassical building of the library is an architectural gem and a symbolic landmark of the city of St. Petersburg. In its depths, the library preserves an impressive collection of Hebrew manuscripts, including significant examples like the Codex Babylonicus Petropolitanus. The National Library of St. Petersburg has established itself as an important research institution and houses treasures from various eras and cultures.

The National Library of St. Petersburg is easily accessible by public transportation and is located in the heart of the city, close to Nevsky Prospekt. It attracts both national and international researchers and scholars seeking access to a wide range of Hebrew writings. The library places great importance on the protection and preservation of its valuable heritage, utilizing modern technologies to facilitate access to the manuscripts. As a place of education and culture, the National Library of St. Petersburg plays a crucial role in preserving and disseminating knowledge and cultural heritage, serving as a treasure trove for those interested in history and literature.